All Nonfiction

- Bullying

- Books

- Academic

- Author Interviews

- Celebrity interviews

- College Articles

- College Essays

- Educator of the Year

- Heroes

- Interviews

- Memoir

- Personal Experience

- Sports

- Travel & Culture

All Opinions

- Bullying

- Current Events / Politics

- Discrimination

- Drugs / Alcohol / Smoking

- Entertainment / Celebrities

- Environment

- Love / Relationships

- Movies / Music / TV

- Pop Culture / Trends

- School / College

- Social Issues / Civics

- Spirituality / Religion

- Sports / Hobbies

All Hot Topics

- Bullying

- Community Service

- Environment

- Health

- Letters to the Editor

- Pride & Prejudice

- What Matters

- Back

Summer Guide

- Program Links

- Program Reviews

- Back

College Guide

- College Links

- College Reviews

- College Essays

- College Articles

- Back

Hyphen MAG

“Why don’t you treat me like everyone else?”

“Maybe if you were actually Chinese you would know.”

I sit silently in the back seat as his answer, dripping with contempt, festers in my mind. Biting my lip, I turn to stare out the window. Our translucent reflections hover in the glass, and I wonder how the boy sitting next to me can think we are so different. We share the same onyx hair, angled eyes, and golden tan, yet his words have erased any hint of solidarity between us. Like the cars hurtling past, I wish that the question, demanding to be resolved, would simply fly away.

Who am I?

Genetically, of course, the answer is simple. My mother is from Guangzhou, and my father from Hong Kong. They met as immigrants and had me and my older sisters, Diana and Karen. My blood is as Chinese as the waters of the Yangtze River. But the ever-changing, elusive concept of cultural identity is never complete with just 23 pairs of chromosomes.

•••

I sit in my room, dutifully working through my daily pre-algebra problems. Downstairs Mom is cooking my favorite dumplings; she promised if I work my hardest, I’d get two extra for lunch. According to her, academic excellence is a tradition my sisters and I need to begin now. After all, Diana, Karen, and I are the first in our family to be born on American soil.

A door slams. I hear Karen’s voice, but it’s garbled, twisted, raw. I peek downstairs.

“Who did this to you?” My mom demands in a voice that is somehow equal parts empathy and fury. She grabs the rotten apple and tenderly caresses the newly forming bruise on Karen’s forehead.

“I-I don’t know,” Karen sniffles. “I was just walking home, and some kid shouted at me and threw it.” After a moment of silence, she looks into my mother’s concerned eyes.

“Mom, what’s a chink?”

•••

My sisters and I are dressed in traditional robes for Chinese New Year. I love the feel of the intricately woven silk, the brilliant crimson and blue hues. Six years mark me as the youngest, so I stand in the back while Diana leads our mini-procession into the living room. There, our parents are seated with the red hongbao envelopes filled with money.

My eldest sister is the first to step forward. She bows, palm flat on palm, and dutifully recites the dictum expressing thanks and good luck to both of our parents in perfect Chinese. I hear them repeat the phrase back to her and the sound of two fat packets landing in Diana’s open hands. Karen does the same.

I move forward reluctantly. I am the only child who can’t speak fluent Cantonese. In order to better understand the culture of her children, my mother has tried her best to assimilate into America, gradually transitioning from Chinese soap operas to “The West Wing.” She saw language as a path to becoming a better parent, enabling her to participate in our school and its sports activities. By the time I was born, English was common in our household, and today, my Chinese vocabulary is embarrassingly limited. Nevertheless, I bow, close my eyes, and slowly begin to recite.

“G-gong hay f-fat choi.” Painfully aware of my thick American accent, my voice lifts at the end of the sentence, already asking for leniency.

Trembling, I raise my head to the surprising sound of my parents’ laughter. My mother reaches out and pats my scarlet cheeks as I exhale in relief. “We know what you meant, siu laumong,” my father says, affectionately using my nickname “little rascal.” They hand me my red packets.

•••

“And that’s how I got forty-five!” I finish with a smile and final flourish of the purple Expo marker. I turn around at the front of my third-grade classroom and am met by blank stares. Apparently, my impromptu lecture on multiplying by nine has not gone over well.

Someone snickers. I slide back into my seat, and a familiar whisper, slipping through the spaces between cupped hands, finds its way to my ears: “Are all Asians like that?”

I smile. It’s a refrain I will hear for the rest of my academic career, but in a way, it makes me almost happy now. Before, I used to lash out at comments like this, but I have learned to stay thick-skinned after my sisters’ encounters with the same stereotypes. My parents have shown me that surrendering to anger accomplishes nothing, opening my eyes to the reality that one ordinary boy cannot stop widespread ignorance. Instead, they taught me to view these comments as compliments. If Asians are seen as successful and smart, why not take pride in it?

•••

My mother and I arrived only a month ago, yet I’m already hearing the wheels of our full suitcases screech across the glossy marble of my grandparents’ apartment for the second time. My mother has served as translator for the past few weeks, and thanks to her, the language barrier melted away as I chatted with my grandparents over steaming bowls of rice and pork. I’ve never felt so at home in Guangzhou, with America and the fifth grade literally a world away.

“Is there anything you want me to say before we leave?” Mom asks softly, rubbing her reddening eyes.

“You’ve said so much for me already,” I say. “Let me take this one.” Walking over to Gong Gong and Po Po, whom I knew I may never see in person again, I embrace their frail bodies one last time to thank them – this time, in their native tongue.

“Gong Gong, Po Po…xie xie.”

•••

Grabbing the handle, I nearly rip off the door to my mailbox. My heart is beating faster than my hands are shaking. The envelope is thick, but I tell myself not to jump to conclusions as I race home. I tear the orange folder, snatch the top paper, and begin to read. My eyes fly over the obligatory “thank you” and straight to –

… accepted into the High School for Science and Technology.

I can barely hear myself shouting. Like the embraces of my family members, waves of excitement, relief, and joy swallow me whole. My mom laughs. “Who would have thought all three of my children would attend the best high school for technology?”

She calls Gong Gong and Po Po with the good news first, and then barrels through an impressive array of calls. Relatives express congratulations, alternating between English and Chinese. I’m lucky my parents take over the calls, giving me a chance to catch my breath. One voice in particular, thankfully in English, says: “Keep doing what you’re doing. You are making us proud to be Huangs, and proud to be Chinese.”

•••

“But you’re not Chinese, so you don’t understand.”

A knot of pain tightens in my stomach. My mom’s friend from Guangzhou and her son are visiting the U.S., and we are driving them from the airport to a relative’s house. While my mother chats with her old friend, I have tried to introduce myself to this boy, but with each attempt I am met with laughter. He mocks me, parroting my voice in the Chinese he knows I can’t understand. The few words I can make out are “ugly,” “stupid,” and “American.” Here I am, facing rejection from a member of the very community I so proudly identify with, the community I have endured racial slurs for, the community of my loved ones.

But this pain isn’t new. If anything, it’s simply the peak of a slowly growing mountain. I’ve experienced years of tacit exclusion from conversations with friends and family, parents who meet me and begin to complain about American whitewashing. “Such a shame,” I’ve been told. “Such a shame you can’t speak Chinese.” To the Chinese, shame is a loaded word.

When we arrive home I am burning with emotion. I attempt to race upstairs before my mother can sense what’s wrong, but there’s no escaping the eagle eyes of a tiger mother.

“Matthew, is there anything you want to tell me?” She asks. I turn and sit next to her.

“I’m fine, Mom.” I hesitate. “I just have one question.”

“Shoot.”

I lower my voice. “Promise you won’t laugh?”

She stares at me, then nods.

“Am I Chinese, or am I American?”

•••

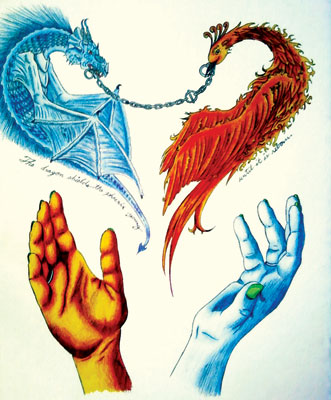

The next day, I wake up with a renewed sense of purpose. After thinking about what my mother told me, I feel as if I finally belong. My identity cannot be dichotomized; I am Chinese-American. I refuse to believe, as I have for much of my life, that a hyphen is a symbol of mutual exclusivity. That hyphen, insignificant as it seems, is a symbol of connection. It is a bridge that I, my sisters, my parents, Gong Gong, Po Po, and millions of others have crossed because the simple happiness we share, whether it is felt on Independence Day or the Mooncake Festival, cannot be contained by oceans and borders. I know who I am.

I can’t tell you who you are. Nor can your father or anyone else. You must decide for yourself. But know this: your culture won’t come from your tongue. It’ll come from your heart.

Similar Articles

JOIN THE DISCUSSION

This article has 1 comment.

Being Asian-American has affected me in an incredible number of ways. It's informed so much of how I interact with others, and how I think of myself within the global community. It is something I cherish, yet for so much of my life, I felt as if that identity was constantly being challenged. This memoir is about how I grew to accept myself, and I hope you enjoy! (Names have been changed for confidentiality).