All Nonfiction

- Bullying

- Books

- Academic

- Author Interviews

- Celebrity interviews

- College Articles

- College Essays

- Educator of the Year

- Heroes

- Interviews

- Memoir

- Personal Experience

- Sports

- Travel & Culture

All Opinions

- Bullying

- Current Events / Politics

- Discrimination

- Drugs / Alcohol / Smoking

- Entertainment / Celebrities

- Environment

- Love / Relationships

- Movies / Music / TV

- Pop Culture / Trends

- School / College

- Social Issues / Civics

- Spirituality / Religion

- Sports / Hobbies

All Hot Topics

- Bullying

- Community Service

- Environment

- Health

- Letters to the Editor

- Pride & Prejudice

- What Matters

- Back

Summer Guide

- Program Links

- Program Reviews

- Back

College Guide

- College Links

- College Reviews

- College Essays

- College Articles

- Back

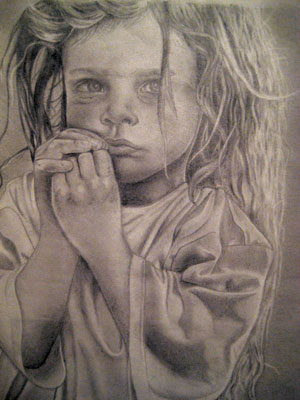

Little Girl

I see the little girl for the first time one rainy, autumn day when the world is sleek with mud and the Theoy confetti of wet, fallen leaves and everyone should be inside.

I am taking the trash out to the curb when I feel her eyes on me. The little girl stands across the street, her thin frame shrunken inside the hollowness of her shabby dress. I wonder what kind of mother would let her child out in the weather.

“Hi,” I say, before I turn and I dump the stinking bag in the canister and turn around long enough to see her flee, a mop of dirty brown hair streaming behind her in the wind.

I shake my head and go back inside. The smell of rain and earth and iron comes back with me into the house and I cannot shake the feeling that I stink of blood for the rest of the day.

***

Our dog, Spike, dies two days later. My son, Theo, and I find Spike as we are leaving the house for the school bus. I had let the dog out in the morning as I always do, expecting him to do his business and return scratching at the door, eager for his breakfast. When he hadn’t returned promptly, I had been a little surprised, but there were squirrels to chase and a lunch to pack for Theo and I didn’t worry much.

He is lying on the front steps, so naturally that he might be sleeping, but when Theo bends down to pat him, his hand recoils.

“He’s cold,” my son says, and then he starts to cry.

Suddenly, the morning has turned dark. I take my child, who is wailing now, inside. My heart hurts, my head hurts. As I turn to go, stepping over the body of my dead dog, I see the dark-eyed girl peering out at me from behind the bushes across the street. She shakes her head sadly.

***

Theo sees her for the first time a few days later when we are out for a walk. He is not taking the death of Spike well, and I am trying to keep him busy, distracted. We are out on the premise of looking for toads.

She is digging furiously in an empty lot with her nails, her hair plastered against her face. She does not see us.

“That looks like a fun game,” Theo says observing the little girl.

“A dirty one, for sure,” I say grimly.

“Can I go play?” asks Theo.

I shake my head. I tell him we don’t know her. I tell him we are on a walk. I tell him she looks like she is having fun on her own.

“Don’t play with her,” I tell him later when he grows insistent. I shouldn’t have. They always want to do what you tell them not to.

***

Theo makes friends with everyone—the children at his school, the old woman at the grocery store, the man at the gas station. He is a friendly, trusting child and I am proud of the way he makes friends. I can’t blame him for making friends with the little girl. Maybe I shouldn’t have let him outside that day, but if he hadn’t gone out then he would have met her the next day or the day after that.

I tell myself I am a bad mother for wishing he wouldn’t be so friendly to the wild girl who hangs out on the street. They run, screaming with laughter, down the sidewalk one day, and sit silently together the next, counting blades of grass. The next day, I see her wrestling with him in the frosty October dirt. There is something about her that unnerves me…that wild shock of hair and the way her teeth seem to glitter. I can’t believe I wish Theo would come inside and play videogames.

On the third day that my son and the girl play together, I watch them from the kitchen window and almost call Theo in. But then I tell myself I am a bad mother. It’s only a little girl, and a sorry one at that. I tell myself that maybe she needs a friend…after all, I never see her parents, and she never wears new clothes.

That night, all Theo will talk about is “the new girl,” but he doesn’t know her name

***

“This is my friend I was telling you about,” Theo, says earnestly, “can she come in?”

My son stands beside the little girl, cheeks scrubbed rosy and belly round against his shirt, a stark contrast to the frail dirty thing next to him.

“He said you have cookies,” she says. It is the first time I have heard her voice. Her voice is dull. For some reason, it reminds me of unpolished bone.

“You do have cookies, don’t you?” Theoa asks anxiously, “You still have the ones from the store?”

“Of course I do,” I say. My son nods solemnly, and smiles. He expects me to let them in and let them have a tea party like he and his friend Tommy did last week. Tommy was a boy from the next neighborhood over with pale freckled skin, a starched shirt, and a mother who shared my interest in finding the best coupons for our growing boys’ never-ending wardrobe needs. This is different, but I force a smile and open the door. “Come in,” I tell them, “I’ll put the kettle on.”

The little girl sits primly at my kitchen table. She is very pale, her little sparrow bones pressing close to her flesh as if for warmth. Her dark hair hangs all about her down to her waist.

I look at her thin arms in short-sleeves as she reaches for a cookie.

“You must be cold,” I say.

“No,” she says brightly, “I never am.”

She doesn’t eat the cookie, but holds it carefully in her hand as if she is afraid to see it crumble. Looking at her, I think she must be hungry, but I never see anything actually go in her mouth.

***

I am out raking leaves when I see Mrs. McGregor. She lives across from us and has a husband suffering from Alzheimer’s. We’ve had her over for dinner once.

“Hi, Anna,” she says, but she doesn’t seem as bright as usual.

“Hi!” I say, “Something wrong.”

She frowns, “Yes, I guess so. It’s Delilah.” Delilah is her fat, yellow cat who spends the summers on her porch in the sun and the winter in front of her fireplace.

“Oh,” I say, pausing my raking, “Is she sick?”

“No,” Mrs. McGregor says, “She’s dead.”

“Dead!” I say, “Oh, that’s awful. Did she get run-over?”

Mrs. McGregor blinks back tears.

“No, I found her in the backyard this morning. She was just dead.”

“That’s terrible,” I say.

“It is,” she says, “it is. But then you would know, what with poor Spike and all. The Harrisons lost their terrier the other day too. Maybe there’s some flu going around.”

“I hope not,” I say.

Children’s laughter rings from across the street.

***

Theo does not grow tired of the little girl as I had hoped. Instead, he begins to spend more time with her and less time with his friends from school. In a way, it makes sense. Theo has always been very conscious in his role of wanting to help. Even when he was a little boy, he was eager to aid me clean the house or carry the groceries in. Every injured bird needed to be bettered, every tear kissed away, every right made wrong. After the divorce, he was especially passionate. In his own, little boy way, he made sure I was tucked in at night and had coffee in the morning. It’s only natural that he has been drawn to a new person who needs his help. It’s in his nature.

It’s getting colder outside, and I tell Theo he should be inside, playing Super Mario and Clue and doing his homework, but he wants the cold on his cheeks and the little girl’s laugh in his ears.

She is always waiting for him when he comes home from school. And Theo will run after her breathlessly, only to spend the afternoon climbing trees and fighting with sticks and sometimes, just talking very earnestly.

“She tells me things,” Theo says one night as I am kissing him goodnight, but when I ask what sort of things he won’t say.

“Don’t worry, Mama, they’re good things. Just about old people. Old places.”

I don’t understand, but I smile and nod and turn out the light.

Something flickers for a moment against the window of his room and then is gone.

***

I think as my son’s affections grew for her, so did mine. It certainly helped that she became a regular at the house when it got too cold for Theo. They would help me bake cookies and vacuum the house. Later they would go to his room for hours. Sometimes I would hear her singing, other times growling. Whenever I came to check on them, though, they would always be sitting quietly.

The little girl is very sweet. She brings me dead flowers, frozen in the frost, and hugs me with a fierce tightness that suggests for a few moments, every-time that she will never let me go. We grow closer over time. She starts to call me Mama, like Theo does, and I don’t stop her.

I begin to worry less about the girl and more for her. She doesn’t seem to go to school. She doesn’t look well fed. Christmas is coming, and frankly I wonder if she’ll be getting any presents.

The little girl is talkative enough, telling me about how to clean my grandmother’s silver and the amount of eggs to put in a crepe recipe, but when I ask her about her parents she is oddly silent.

I ask her if her parents mind that she spends so much time over at my house, but she only shakes her head and smiles.

One night when she has stayed until long after dark watching movies with my son, I tell her I should take her home.

“You can’t go out at this time of night alone,” I tell her, “I’m sure your parents wouldn’t like it.”

“It’s okay.”

“No it isn’t,” I say barring the door.

“Where do you live?”

She shakes her head and wriggles out of my grasp and into the night.

I think of calling her name, but I realize I don’t know it, still.

That’s when I decide to call Child Services.

***

The social worker wears a tight red suit that matches her severe, almost bloody lips. Her turtleneck is too tight about her throat and her chins hang down, wobbling with every word. She smiles in a tense way.

“So, you say there’s a little girl…”

“Yes, “ I say. I want to add that she is Theo’s friend, but that seems wrong, in front of the woman’s accusing stare.

“How long have you seen her?”

I think about it, “Maybe for three months or so. She’s always out, everyday. She doesn’t look like she gets enough to eat.”

“I see,” says the woman. She writes something in her folder and shakes her head. “I wish you had come to us sooner. Three months is a long time for a child to be neglected.”

I feel judged, “I’m sorry,” I say, “I just didn’t—I didn’t realize how bad it was.”

The woman nods, “We never seem to realize what great evil is taking place just before our eyes. Somewhere, in this neighborhood, that little girl’s parents are wasting their time on drugs, most likely instead of feeding their child. ”

I shake my head, “It’s sad, so sad.”

The lady nods firmly and busies herself with her writing.

“What will you do next?” I ask after a second.

She fixes me with a beady-eyed glare. “The proper thing to do is take the girl into state custody, until we can identify her parents. Afterwards, however, I believe she will be placed in foster care or a residential living facility until further proceedings.”

My heart shrinks. I think of the wild little girl, who loves nothing better than the dirt and the cold air and the darkness imprisoned in some dark room with a blaring television and angry adults who can barely stand her.

The woman stands up, “Where do you think I can find her?”

“I-I.” I can’t do it, I can’t do it to the little girl, to Theo. I swallow, “Could we foster her? She’s friends with my little boy. She feels safe with me. We could take care of her for a while.”

The old woman arches an eyebrow, “That could be possible, if you fit our qualifications.”

As it turns out, it is.

***

Theo is thrilled when the little girl moves in, but the little girl is not so pleased. Although she seems happy when I show her the redecorated guestroom and the new sets of clothes, the little girls seems angry when I tell her she has to stay in the house at night. At first I think it is because she want to stay with her parents, but when I ask her, she shakes her head.

“I’m just afraid I’ll mess up,” she tells me later when I press the subject.

That touches my heart, and I hug her tight, feeling her tiny cold body against mine.

“You won’t mess up, sweetheart,” I tell her, but there is fear in her eyes.

The little girl will start going to school with Theo after Christmas break. For now, I focus on making her happy. We make ginger-bread houses, decorate a tree, and watch the Christmas Story.

Theo is the happiest I have ever seen him. He calls the little girl his sister and romps about with her through the house and out into the yard. They play hide and seek and chase and some game the girl knows called Tom Tiddler’s Ground. The afternoons are always happy, but I begin to dread the evenings.

Despite my varied attempts at cajoling and sternness, the girl won’t eat. She picks at her food and when she does finally force down a piece in the attempt to please me, she looks ill. I worry about her and make a doctor’s appointment for after Christmas. In the meantime, I fight a desperate battle in the kitchen trying to come up with something the little girl will like.

The little girl is well-behaved and painfully polite, but she grows strange at night. I let the children stay up late reading and whispering and joking, even though I know I shouldn’t, because they are so happy. But the girl never seems to grow tired and when Theo finally droops into sleep, she grows wild. I keep finding her trying to go out into the darkness, and she grows wild when I tell she cannot leave. One night, around two in the morning, I hear the window in the guestroom slide open.

By the time I get out of bed, the little girl has disappeared into the night.

***

Christmas comes in a happy, sugar rush of noise and gaiety. I heap presents on the little girl, and by the end of the day, she is smiling her odd little smile, surrounded by china-dolls and dress up clothing. Theo is his normal happy self—he has blossomed with the little girl here. I had feared in the beginning that taking her into the house might affect him in some negative way, but he seems happier every day. That night, after carols and hot chocolate I go to sleep exhausted by the children’s antics but very pleased. As I drift to sleep, I hear Theo and the little girl still talking in the living room.

They are laughing about something the little girl has been telling Theo—something about putting candles in the Christmas trees—when I hear the little girl abruptly tell Theo he should go to sleep.

“I’m so hungry,” the little girl says.

I am numb with sleep, but as I fade away, I realize it’s the first time I’ve heard the little girl say that.

The next morning, there are little foot-steps in the snow leading away from our house.

***

The little girl’s night-time escapades are troubling, but they are easy to forget during the day. I read on the internet about neglected children, and figure her urge to go outside must be a combination of anxiety and some childish whim.

The morning after the window-incident, I have a serious talk with her about going out, and she promises not to do so again. Just to be sure, I change the locks on all the windows on the house and the door as well. At first things seem to go well. A few nights pass with no occurrences. The little girl even eats some steak at dinner, which makes me happy. I decide to make steak more often.

On the third night, however, things get worse. I wake in the bruised light of very early morning to the sound of crashing and a strange raspy flapping.

Theo is shaking me. He sound scared.

“Mama, I can’t find her anywhere,” he says.

“Okay,” I mumble sleepily, “stay here.”

I stagger into the living room. Picture frames lie on the ground, books are splayed on the floor. I stare for a moment, not comprehending. Then I hear a scuttling above me and look up. There is something alive, up there in the darkness…it slams into the walls and bashes against the window.

I feel Theo beside me, his hand is clammy as it grasps for my own.

“I think it must have flown in,” he says.

I unlock the window in the living-room and whatever it is flies out immediately into the night.

Theo runs to find the little girl but she is not there.

***

It’s Boxing Day, but there is no after-glow from Christmas. Theo, usually so carefree, is tense and troubled. The little girl is silent and sorry. She returned at four in the morning from wherever she had been, but did not seem surprised to see me waiting for her. When I asked how she got out, she said she had climbed out a window. I told her about the thing in the living room and she said it must have gotten in when she left. None of this made sense, since the window had been closed and locked from the inside when Theo and I woke up, but I ignore all of that, pushing it aside for later.

“But why did you leave?” I ask the little girl, “Don’t you know how dangerous that is? Aren’t you happy here?”

She looks down at her lap. “I’m sorry. I am happy here”

We’ve had this conversation before but I try again, “So you won’t leave again?”

She just looks at her lap.

The little girl is a sorry sight. I can’t imagine how afraid and confused she much be. My anger shifts into concern and I pull her into a hug. She sniffles a little and mumbles something. I tell her it’s alright, but as I hold her, I flinch suddenly flinch back.

Her breath is hot and heavy and filled with something terrible.

“Is everything alright?” she asks, concerned.

I try to smile, but I have to force it.

“Yes, yes. Of course. Just don’t scare me like that again.”

***

After that, I stay up, every night in the living room with all the lights on. The little girl can’t leave without me knowing and so she doesn’t.

By the third day, I am exhausted, despite endless cups of coffee and light naps during the day.There are four more days left before Christmas vacation finishes for Theo and the little girl begins school. I try to stay positive, but I cannot help but feel that something has changed, though I’m not sure what. As the days go on, the little girl grows sulkier and more silent. Theo tries to iniate games of all sorts, but she grows more and more irritated with him.

Finally, Theo gives up on the little girl and spends his days in the basement playing on his Wii. The little girl lies on her bed all day.

I try to get her to come and help me in the kitchen—try to engage her in conversation, but she is lifeless. I worry about her and wish that the doctor’s appointment would hurry up. I tell the little girl to eat more, to sleep more, but she does neither.

Finally, one day, she asks if she can go for a walk. It is a beautiful, sunny day for December, and I tell her she can go if Theo will go too.

Theo seems happy that the little girl is finally ready for fun, and the two leave hand in hand. I watch them go and cannot help but think that the little girl looks slower, smaller, almost dimmer. She should be thriving with me, not falling apart. I feel guilty, as if I am doing something wrong.

Mrs. McGregor stops by the house with a plate of brownies. She has been doing it a lot since I took on the little girl. I tell her not to, but she is the kind of person who will do kind things for you whether you want to or not.

“You look exhausted, dear,” she says as she sits down on my couch for a chat.

I find myself pouring out my frustrations as she tsks understandingly and occasionally shakes her head.

“You’ve certainly got a lot on your hands,” she says when I finish telling her about my troubles with the little girl, “Why don’t you let me babysit them tomorrow? You need a day to yourself.”

I protest. After-all, she has a sick husband to look after, but as I said, she is the kind of person who is stubborn in their sympathy.

At last I sigh and give in and say that would be wonderful.

Later, Theo arrives alone at the door breathless. He says the little girl ran away after a cat and he couldn’t catch up with her. He cries. He tells me that she is mean to him now and he doesn’t understand why.

I try to comfort my son even as I worry about the little girl. I cannot help but wonder if taking her on as my responsibility has been a terrible idea.

***

When the little girl doesn’t return to the house by the six in the evening, I go out looking for her. Theo stays home with a movie, and I feel bad leaving him when he is hurt and frustrated, but I can’t just let the little girl run loose in the streets. There are all sorts of terrible things that come out at night.

I walk down the sidewalk, with a flashlight, calling for her. A cold wind slaps my cheeks raw. The stars are very bright.

I walk for far too long until I find her, curled up in little hole in the dirt of an abandoned lot. There is dirt gathered about her, almost like a blanket and for some reason that scares me. When I reach out to touch her, she is so very cold and still that I am reminded of Spike and I begin to shake.

“Wake up,” I say, shaking her roughly, “wake up.”

Her eyes flicker open and she smiles her strange little smile, “Mama,” she says dreamily, and I am rather touched.

“What in the world are you doing here?” I say.

“Oh…” her voice is very small, “I was trying to catch a cat, but I couldn’t. I was too slow. It’s because I’m so very hungry, you see..”

She drifts off again, I pick her up, terrified. In some strange way, that I don’t understand, I am scared of her and scared for her at the same time, and for a moment the two sides are competing. I feel her shiver in my arms, however—spasm more like it, and my concern for her wins out. I wrap her in my coat and walk home.

Theo has gone to sleep when we get back, and the little girl sits in the kitchen hugging her knees.

“So hungry, so hungry,” she whispers. “Help me, Mama.”

“Sweetheart, just tell me what you want,” I say frustrated and frightened, “tell me what you want and I’ll go to the store and get it right now. Whatever you want.”

But the little girl just hugs her knees and shakes her head and won’t eat anything.

Eventually, I tuck her into bed, and take up my vigil on the couch. It is a long night.

***

Around three in the morning, I am dozing off while CNN plays in the background when I hear the little girl awake in her room.

She is sobbing.

“I can’t, I can’t, but I have to! I have to!”

I go into the little girl’s room and she sees me and instantly quiets.

“I thought you were sleeping,” she says.

“No,” I say.

We look at each other.

“Please tell me what’s wrong,” I say. “Tell me and I will do everything I can to make it better.”

The little girl is silent and I sit down beside her and put my arm around her skinny shoulder.

We sit that way for a long time until the little girl’s breathing slows. Her head wobbles closer and closer to my wrist until she is slumped and I think she is asleep. It is an uncomfortable position, and I am about to tuck her into bed properly when I feel her breath, surprising hot against the skin of my arm. I feel the scrape of teeth, and horrified instantly pull away.

She looks surprised herself.

“I’m sorry,” she mutters.

I don’t know what to say. I don’t understand.

“Will you be able to sleep?” I ask.

“Yes,” she says rather numbly. “Sorry.”

I go back into the living room. CNN is still on, but I watch the little girl’s door for the rest of the night.

***

The next day, I am torn between not wanting to let the little girl leave the house and desperately wanting to get some space from her.

In the end, I call Mrs. McGregor and ask her if her babysitting offers still holds and if so could she only watch the little girl? Mrs. McGregor is obliging, and comes to my house early in the day. She leaves with the little girl and promises of teaching her how to knit and bake a bundt cake. There is a wild eagerness in the little girl’s eyes, so I don’t feel too guilty as I watch the two cross the road over to Mrs. McGregor’s house. Maybe we all need a little space.

I spend the day giving Theo a good time. We drive out to the nearest amusement park and Theo happily spends the day stuffing himself with cotton candy and spinning himself sick on carnival rides. Watching him, I realize how long it’s been since I’ve had him to myself. I have grown to have a certain affection for the little girl…even something that might be called love, but now as I watch my son careen happily on a ride, I realize how much the girl has added stress and strain to our otherwise happy lives.

By the time we are packing into a movie theatre to finish off the day with a generic blockbuster and more sugar, I have resolved to call the social worker when I get home. The little girl deserves a higher level of care then I can provide and Theo deserves a childhood where his mother isn’t completely distracted. Neither the little girl nor Theo may understand at the moment that I’m doing this for their own good, but they will someday and that’s all that matters.

I’m feeling relaxed and happy as we roll into our garage. Theo is grubby and sticky and still euphoric from the day. We go inside and I realize how late it is. I tell Theo to go take a shower as I go to the phone to call Mrs. McGregor.

She takes a while to pick up, and I spend the time thinking of how best to break the news to Theo and the little girl. Should I tell them alone or apart? Right as the social worker comes to pick up the little girl or a couple days before? Should I—“Hello?! Hello? Is this the ambulance?” Mrs. McGregor’s voice blares into my ears, tearful and frightened.

“Regina! Regina! What’s wrong?” I ask, suddenly frightened that something has happened to the little girl. I remember how weak she seemed when she left. Suddenly I am incredibly guilty.

“I don’t know! I don’t know,” Mrs. McGregor wails “It’s Niall! I think his heart’s stopped. He’s gone so pale. I called the ambulance, but I…I don’t…they haven’t come yet.”

“Oh, God. I’ll be right over,” I say.

I shout a few words to Theo and run out of the house and across the street.

The little girl is waiting at the door she looks lively, her cheeks almost rosy, “Can I go home?” she asks, “I don’t like it over here any more.”

I push past her, through the hall, following the sounds of Mrs. McGregor’s weeping.

I finally find her in a bedroom, hunched over a hospital bed.

An old man—Mr. McGregor—lies cold and lifeless on the crisp sheets, two rosebuds of blood lying coolly on his throat.

I want to go over and comfort Mrs. McGregor but I am frozen in horror. I stare at the old lady, her face contorting into sobs, at the old man, so calm and pale.

“Can I go home?” the little girl calls from the hall.

The little girl. The little girl who was always hungry. The little girl who was afraid she would mess up. The little girl’s teeth brushing my wrist…

It all comes together and I am afraid by how blind I have become.

“What happened? What happened?” Mrs. Mcgregor sobs.

“I don’t know, I don’t know.” I tell her, “I don’t know but I’m sorry.”

I go out into the hall. The little girl looks at me with fear. She sees at once that I know.

She opens her mouth but I shake my head.

“Come on,” I say, “let’s go home.”

***

“I’m sorry. I was so hungry.”

“I know. I know.”

“You can’t do that again.

“I know.”

***

I never called the social worker. I thought about it, thought about it a lot, and in the end I realized that taking the little girl away from me would only be good for me. With us, nobody is in danger. With us, the little girl has someone who understands her. She doesn’t have to lie, or cry anymore. She can be herself.

As the years have passed, sometimes I wonder if I have done the right things. I watch Theo grow bigger and stronger, into a happy ten year old, while my daughter stays as she has always been, a little girl. As I put bandaids on my wrists and leave tunafish out for stray cats and let my little daughter out to prowl at night, sometimes I cannot help but wondering what it would have been like if I had chosen a normal life. But in the end, I think everything’s turned out alright. Theo and the little girl still run like wild things through the woods and stay up late whispering secrets and stories. I’m not sure if Theo understands what makes his sister different from him, yet, but I’m not sure if he would care when and if he does figure it out. She is his sister, and he loves her. He knows she would never hurt him. As for the little girl, I think she’s happy. She understands that with us, she isn’t hurting herself nor is she hurting anyone else and that that is the right thing to do. She calls us her family and we call her ours, and overall life is pretty good.

Sometimes, I worry, though. What will happen to the little girl when we are all gone? Where will she go? Will she wander the streets again, wild and lost and hungry? I hope not. That’s why I’m telling you.

If you see a little girl, let her in.

Similar Articles

JOIN THE DISCUSSION

This article has 0 comments.