All Nonfiction

- Bullying

- Books

- Academic

- Author Interviews

- Celebrity interviews

- College Articles

- College Essays

- Educator of the Year

- Heroes

- Interviews

- Memoir

- Personal Experience

- Sports

- Travel & Culture

All Opinions

- Bullying

- Current Events / Politics

- Discrimination

- Drugs / Alcohol / Smoking

- Entertainment / Celebrities

- Environment

- Love / Relationships

- Movies / Music / TV

- Pop Culture / Trends

- School / College

- Social Issues / Civics

- Spirituality / Religion

- Sports / Hobbies

All Hot Topics

- Bullying

- Community Service

- Environment

- Health

- Letters to the Editor

- Pride & Prejudice

- What Matters

- Back

Summer Guide

- Program Links

- Program Reviews

- Back

College Guide

- College Links

- College Reviews

- College Essays

- College Articles

- Back

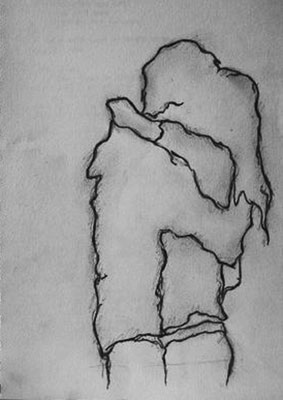

Après Moi

After my brother turned two, my parents decided to spend a night out in the attic of the local tavern. Usually it was only the younger couples who took advantage of the secret room, for fear of being discovered by parents, teachers, or peers, but that one night, my parents joined the trend of secrecy.

However secret it was intended to be, it became common knowledge in town, and it was remembered by anyone who was older than the toddler. The following morning, my father was found dead at the local beach – face down in the water without any known agency and without a note. Generally, it wasn’t discussed, but the one reason I never let it go is because I was conceived the night before.

Not even my mother, the last person to see her husband alive, knew why he did it. My brother and I held a strong chain of silence between us and our mother, and we were the only ones to try to slack it. She never reciprocated, and, privately, I think that it was probably better than openness. We were raised knowing she was miles away, and so we were miles away from everyone else.

In my adolescence I met a boy. He was a friend of my brother and was considered a genius. The entire town knew him for his diligence and eccentricity. I knew him for his pretention. He caused an explosion that blew out a window in his house and mine and he did not apologize. No, he merely paid a visit, winked and me until I blushed, and then sauntered off to befriend my brother.

The other kids my age seemed to find me strange, stranger than the rest of my family. I was colder in disposition, sharper in tongue, and crueler in judgment. And I resembled my father, the assumed-suicidal-maniac who’d rather died than have another kid. Someone once said it was a beautiful way for him to go out, but I didn’t think so.

When I grew older, 16 or 17 or a little more, my peers started to go down to the local beach and play around like it was the tavern attic. They read Bukowski, tried to be special, and, like him, found romantic, short-lived comfort in spending the night at a graveyard.

My brother’s friend, who we all came to know as simply the Genius, never truly cared for me, or anyone. I really like to think he did at some point, but I was proven wrong surprisingly often. I wondered if maybe he was cared of me: felt intimidated by my presence, or my legacy heavy with familial death. I always thought he was the sort of person to be attracted to that sort of thing.

One night I went down to the bay by myself. It was after hours on a Monday night, so none of my classmates would be there. I took off my shoes and looked beyond my feet and into the water, the inlet. It was murky and dark, it had the expensive mysteries of foolish adolescents. The waters moved and shifted, they swam in themselves like tentacles. I could almost see the arms of the priest, the keeper of confessions, being opened, if only I would take a dip myself. But I despised them, all of my peers. Their smiles were protected, but at night their bodies were bare and vulnerable, and they let the water own them, take their secrets. I hated that they didn’t feel they were worthy of owning themselves.

Sometimes, though, I wished I could fall behind myself and let myself be bare, let myself spill my secrets out of every hole in my body for the water to take, like I was a flame, and my privacy, my mind, a joint. The water was itchy-looking and perpetually smiling with the red-eyed vacancy of someone who was irreparably scarred and graffitied over time. It looked as if it had been torn apart, deconstructed and diminished – defaced by carelessness and disrespected, divulgence in what was believed to be divergence – destroyed itself, after it had destroyed another.

“Having a good night?”

I turned away from the murky nothing and saw the Genius. There was a bottle sticking out of the pocket of his jeans and a bruise peeking through the collar of his shirt.

“What are you doing here?” I asked, getting to my feet.

“Considering taking a dip. My whole body feels flaccid and bored.”

His very presence made me feel scandalized. He was such a tool. He was just looking out at the water like it belonged to him, like it was his pride and joy. I thought of myself first, then my father, and started to get heated. He did not own my history, nor me, and he could not break what he did not own.

“You’re horrible,” I said, glaring, as he began to remove his shirt. “This place is like a memorial to my dad, and you’re going to ruin it like everyone else?”

“A flower on a grave isn’t disrespectful.”

“You’re not a flower.”

“And you are?”

I grabbed his forearm and tried to pull him from the water’s edge, and he grabbed the hem of my shirt and played with it, and then I felt a rush that made me decide it was time I learned how my body worked: up against a crag, feet and clothes in the sand, water a safe distance away. It was long-desired feeling being fulfilled, as we breathed heavily, as I was taken. I almost loved it. But there was not climax, no greatness we reached together, unlike how they had made it seem.

After me, he sighed and walked away on shaky legs. I sat in the sand and started to pull on my clothes. I watched him walk so curiously, and saw him at the previous spot on the beach, draw the bottle from where he’d thrown his pants. He took a drink from it, pulled on his pants, and sat down. I rose and watched as he emptied the bottle. I walked forward, but stopped when he stood. He unzipped his pants again, but this time pissed into the water, soiled a crime scene, added to the muck that ruined the water.

“What are you doing?” I yelled, running towards him.

“Taking a leak.”

I shoved his shoulders, and he zipped his pants up. “Not here! Are you crazy?”

He sighed and burped into his hand. “No, no I’m not crazy. Calm down.”

“You’re ruining it,” I said, shoving him again, my knees unstable. I wanted to do something to hurt him, otherwise it wouldn’t feel right, but I was unsteady. “You’re just like the others.

“You just said,” he laughed, “not fifteen minutes ago, that I wasn’t a flower. And neither are you, you know? You messed this place up with my help.” He pointed to the rock on the far side of the beach, and the blood on my leg.

My hands were shaking out of anger. He was wrong. He was so wrong he had to be so wrong. I took the bottle from his pocket and posed it like I was going to swing, and he just laughed before I hit him over the head with it. The liquid and glass scattered around his head, and a little blood dripped from his temple, and the remaining bottle slipped out of my hand. I started to cry.

The water had served as a memorial to my father, he was its patron saint. It was like a church, a place of safety for confessions. Now it had been violated by not only someone I had trusted, but myself, and I felt I had nowhere else to go.

I sat in front of the dark water. The sand under me was soaked and salty with tears like the sand under the bay. Anyone who had been here before – my brother, the genius, my peers – were gone to me now. I hated them so much in those moments, but even more so, I hated myself. I hated that I cried so much, I hated that I’d trusted a genius at all, and I hated that I thought myself separable from my generation, the people, from who I had come to learn by osmosis, that there was beauty in death or wonder in losing oneself when so young. I stood up and though. Before me there was love, there was water. After me was there nothing? I walked forward. I took off my shirt and pants again and sat them in the sand. Then I took off my bra and underwear and wondered, shivering, if I would experience climax. Love wasn’t required to orgasm.

I put my hand first to my breast, then to the center of my chest, and felt my fleeting heart. For the first time ever I waded into the water. After me there would be nothing. I took a deep breath and held it ready to be taken, in place of my father, as the water’s greatest secret.

Similar Articles

JOIN THE DISCUSSION

This article has 0 comments.