All Nonfiction

- Bullying

- Books

- Academic

- Author Interviews

- Celebrity interviews

- College Articles

- College Essays

- Educator of the Year

- Heroes

- Interviews

- Memoir

- Personal Experience

- Sports

- Travel & Culture

All Opinions

- Bullying

- Current Events / Politics

- Discrimination

- Drugs / Alcohol / Smoking

- Entertainment / Celebrities

- Environment

- Love / Relationships

- Movies / Music / TV

- Pop Culture / Trends

- School / College

- Social Issues / Civics

- Spirituality / Religion

- Sports / Hobbies

All Hot Topics

- Bullying

- Community Service

- Environment

- Health

- Letters to the Editor

- Pride & Prejudice

- What Matters

- Back

Summer Guide

- Program Links

- Program Reviews

- Back

College Guide

- College Links

- College Reviews

- College Essays

- College Articles

- Back

Equator

The mound stood out against the surrounding green grass. The people, all family, encircled the mound with their heads down and hands grasped in the hands of another. They looked at their feet, trying to escape reality and pain and withdraw into themselves. Their faces reflected the kind of ache that seems eternal. Silence filled the air, and the only disruption was the light breeze that rustled the leaves on the scarce trees.

Her name was Jane. It’s a simple name, short like her life and the summer night of her death. No one in the family knew her true family. No one knew if she even had a mother or father—maybe she was a child of the spirits. All they knew was that one day she was at their door, a sleeping infant wrapped tightly in a dirty yellow blanket. They took her, fed her, and raised her. But Jane was different in ways from her adopted family. Edith always commented on how Jane walked in a peculiar fashion, practically hopping her way through the fields of sugar cane and maize. Jane never cried either, always patiently waiting for a cookie from her new papa or doing her chores without complaint. The whole village had praised her as the perfect villager’s child, and so, when the news of her death reached them, everyone was miserable, especially during the funeral.

Although the funeral was held a few weeks before, Edith still had to say goodbye to Jane. She was Jane’s oldest sister who lived in America. Being so far from her homeland, Kenya, she could not attend the real funeral, and thus settled for a more private event. However, as tears slowly slid down her cheeks, she was thankful for her delay and the little extra privacy it awarded her. Edith thought of the days when they were young and could run in the fields together, and she wondered why her younger sister had left this world before herself. Even as these thoughts cluttered Edith’s mind, she tried to pay attention to the present. She glanced to her right to see her daughter staring intently at her mother. Edith could do no more than squeeze her hand and slowly close her eyes as she turned back to her shoes.

This daughter, an American, was an outsider. She was born and raised in America, where she learned to cry for television and fight for toys. Her view of the world was strange to her parents and extended family—she was strange. But her relatives, the people standing around her, still accepted her because she shared their blood.

“Let us pray,” an elderly man said, his voice cracking slightly. His skin was black as night, the product of years of toiling and living under the hot sun of the equator. His moist eyes glistened in the sunlight as the wind whistled past everyone’s ears.

As he prayed, the American looked at the mound of dirt and wondered. She had met Jane only once in her life and that was when Jane was cooking dinner. In the dark kitchen-hut, Jane’s face was hard to define as she turned away from the burning firewood to shake the American’s hand. This was the moment the American kept replaying in her head. If only she had actually tried to interact with her aunt, then they might have had a relationship. The funeral would be more than just a funeral for the outsider; it would have an actual meaning to her, just like the meaning Jane’s death had on all of the silent prayers standing in the circle.

The American peered up at her mother to see her lips trembling and eyelids fluttering. Edith was crying again, and, as usual, the American was clueless as to what to do. So, as usual, she mimicked those around her and squeezed her mother’s hand gently, just as her mother had done to her own hand, and her eyes returned to the mound of dirt. The burial site was in no graveyard or distant field. It was right in the center of the family’s land and merely a few feet away from the kitchen-hut and the brick house. Jane had become the literal center of the family’s lives, and she would never be forgotten. The wind had blown Jane into their arms, and they had changed her life as much as she had changed theirs.

“…Amen,” the old man finished. The American’s eyes flickered up to the man, her great uncle, and noticed his face was staring up to the heavens. He looked content and at peace, as if he had not just prayed for a young woman who was alive and then suddenly dead.

“Let us go inside to eat,” said a woman. The American guessed she was her aunt in some way, yet she could plainly see that the stress and sadness of death fought for control over the woman’s once youthful face.

Edith let go of her daughter’s hand to go converse with the rest of her family. The American was confused by the commotion as everyone made the short walk to the dining room, a stark contrast to the complete silence moments before. Alone she followed them, slowly and silently. In the dining room, the windows were all forced open and the open wall left uncovered. The American shivered as the air blew freely around the room and the large congregation sat at a long table. She stared at the large platters of ugali and sukuma wiki being brought out by the women of the household. Immediately, she wondered how anyone would have such a big appetite after saying goodbye to a deceased loved one, but she was an American, ignorant of Kenyan culture.

“I hope you eat sukuma,” one of the older women told the American in her thick Kenyan accent. “You need to fill up before you go back to America.” Then she smiled.

She smiled. It was the first the outsider had seen all day. This old lady managed to smile even when a few feet away her niece eternally rested. But soon the whole room filled with laughter and gossip, as the American saw faces transform from gloomy to bright and cheerful in an instant. She looked in disgust as they ate like fat pigs until their cheeks were sore. All the while, their sister’s cold body laid still in a grave.

The American watched as her mother began to laugh and eat and drink mala like the rest of the family. She was no different, but, as usual, her daughter was the different one. The outsider was the only person to not eat and not speak, because she felt like it was all wrong. Maybe it was simply something the outsider did not know, like Jane. Maybe she was the only person who valued life over food. She did not understand, so she sat in judgment, playing God instead of student.

“I’m going for a walk,” the American said, standing up from the table.

“But you have not eaten!” another relative protested.

“I’ll eat when I come back,” she replied, speaking over her back as she walked out the open wall.

She stomped right past the mound of dirt, glancing only for a moment. She looked forward at the cows grazing the land, incredibly focused on fattening themselves and unaware of the events surrounding them. Staring at them, the outsider concluded that the humans inside were no different from the cows outside. So onwards she went, past the rows of tall, bright green stalks of maize and past the fence encircling the large farm. She could feel the wind pushing her forward and did not look back.

As she moved forward, she did not notice the shattered soapstone carving on the ground ahead of her. In her open-toed shoes, her toe stubbed itself on a protruding piece of Kisii soapstone, almost causing her to fall. She made no sound and turned to see the jutting piece glistening in the sunlight. Around it were hundreds of other broken, jagged bits of soapstone, all once part of something greater and more beautiful. In that moment, she noticed that the wind had stopped blowing and that everything was silent. She removed the piece that had tripped her from the dirt and held it up to the light, examining its beauty and filthiness as an individual piece.

And she realized.

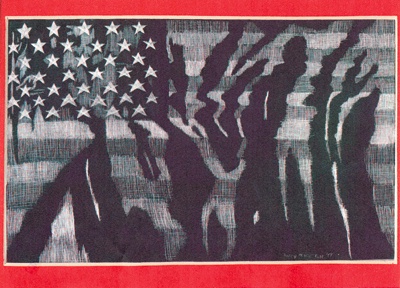

She found meaning in the jagged piece of soapstone. It was a meaning that made her understand. Lucy finally understood that her family was like a piece of art, where any piece missing would make the carving less valuable and less perfect. Her family’s need to congregate and chat symbolized their need to rebuild family ties in an effort to compensate for that missing piece. Jane was a broken piece, and Lucy knew that no matter what, they were family. Lucy was the blood of her family and not the culture of her family, while Jane was the culture and not the blood. They might have never really known each other, but they could relate on those grounds. In that instance, Lucy recognized that she was just as important a piece to the art as Jane and her mother and the old praying man. No matter how strange her own American customs and beliefs were to her family, she was still an invaluable part of that sacred union.

So, Lucy pocketed the soapstone and turned around, walking calmly back to the house of her family.

Similar Articles

JOIN THE DISCUSSION

This article has 0 comments.