All Nonfiction

- Bullying

- Books

- Academic

- Author Interviews

- Celebrity interviews

- College Articles

- College Essays

- Educator of the Year

- Heroes

- Interviews

- Memoir

- Personal Experience

- Sports

- Travel & Culture

All Opinions

- Bullying

- Current Events / Politics

- Discrimination

- Drugs / Alcohol / Smoking

- Entertainment / Celebrities

- Environment

- Love / Relationships

- Movies / Music / TV

- Pop Culture / Trends

- School / College

- Social Issues / Civics

- Spirituality / Religion

- Sports / Hobbies

All Hot Topics

- Bullying

- Community Service

- Environment

- Health

- Letters to the Editor

- Pride & Prejudice

- What Matters

- Back

Summer Guide

- Program Links

- Program Reviews

- Back

College Guide

- College Links

- College Reviews

- College Essays

- College Articles

- Back

Retribution

The boy watched from a distance; it frightened him too much to get too close. A small crowd gathered in a circle, alike in their stained strips of cloth that covered their filthy brown bodies. The silent souls looked down at the object in their path with different expressions; reverence, pity, sadness, fear. But the boy just stood with a blank stare, the scorching sun beating salty sweat into his eyes, glistening in his messy dark hair. His skin burned, his feet torn. People on breaks from their work, carrying heavy tools and heavy hearts, made their way down the sandy path to the narrow huts where workers of the boy’s status lived; some called them servants or workers, but the boy knew: they were slaves. The home-comers, men, mostly dwindled over to the spectacle, and slowly women trickled out of the houses.

Finally he heard a desparate cry and knew she had discovered the source of the gathering. “Moshe!” she cried, the crowd parting like waves in the Red Sea for her. She knelt by the man who lay there motionless, his eyes closed in peaceful, welcoming sleep, and his lips slightly parted. He bore no signs of blood or physical injury, but he was an old man. After a certain age, the men struggled with the ardurous work their cruel kings set upon them. When it became too much, sometimes they would simply collapse from the strain. Others had their lives drained from them from the sun’s deadly beams, and died with their throats dry and hands clenched. “Moshe, Moshe,” the woman cried, rocking back and forth. She was much younger than her husband, and still had some of her youthful beauty. Their marriage had not been uncommon because of their age difference, but because before consulting her father for her hand, he had asked her. No woman had ever been asked for her consent, not even the natives of the land.

She let tears fall from her face and her hair fall from its cloth unashamedly, oblivious to the people around her. Some bowed their heads in respect, others drifted away with blank fear on their faces at the sight of the disheveled woman. She began to sing softly, in the language of her land, a language the boy only knew a little of. He caught a few words and recognized that she sang a prayer, but his mother never taught him words of her native language.

“What is this mob?” spat someone, the sound of grating metal coming from behind the boy. The people turned to see one of the king’s guards, his gold-colored armor glinting like firelight in the sun. “Why do I hear your filthy language, immigrants? Are you so cretinous you cannot learn the language of the emperors after years of petty servitude in our glorious land?” He shoved past the boy toward where Moshe’s wife still lay on the ground, immersed in her grief. She ignored the guard, most likely not paying attention that he was there, and buried her face in her knees, her hands touching the ends of his hair. The guard grunted when he saw the body of Moshe; he was another faceless alien slave, and now he just had to figure out what to do with his body. Frankly, the guard privately thought that having their captured people work as they did was unwise. They were more trouble than they were worth. They worked hard, but were as mortal as any man and nothing the hard, physical work that was beaten into them. He ordered a few other guards to drag the man’s body away, and after a few chastising barks from the guard, the rest of the crowd dispersed. Another young woman, a friend of Moshe’s wife, whispered reassurances and half-carried the unhinged woman into her hut, where racking sobs could still be heard hours later.

The boy, forgotten in the crowd, still stood unmoving. To the people that enslaved them, even his own people, Moshe was just another body, just another man. But to the boy, he was so much more. Orphaned at a young age, Moshe, who had never fathered any children, had adopted him as a son. But beyond that, he had been a mentor, a teacher to the boy. Moshe was a fascinating man – he believed in freedom and equality and liberation, and believed that a single man strong enough could free them all of this hard life of sweat and dust. He believed somewhere in the heavens was a single man who could do anything he wished, with the power to create the universe. Like the king’s gods? the boy had asked, slightly familiar with their strange, beast-bodied deities that had magnificent temples created in their honor.

“Yes,” Moshe had replied, “but this man is special, because there is only one of his kind.”

“One god,” the boy had pondered. “He must be very lonely.”

Moshe had smiled, his chapped mouth splitting into a wide grin, his head thrown back in delight over the young innocence of the boy he’d saved from the fate of young borne orphans – death by drowning in the river.

“Yes, he was – but he was very powerful, and so he created the universe and everything in it from the darkness to keep him company.”

At night, when the workers were given a few precious hours to eat and sleep, Moshe would tell delightful stories to the boy, about the wonders of this God, the amazing things he could do. God did not believe that Moshe’s people were inferior – in fact, God’s sacred people were the persecuted, the victimized and the oppressed. Moshe, a gifted, intelligent man, despite his impoverished background, taught him the gift of language and writing, and all about life and death he knew, to which the boy began to lose faith. His life would be spent as an anonymous outsider, and no one knew the perils he would face after death. The natives, their masters, believed they would face an eternity of punishment, if not because the boy’s people did not worship their gods, but because their bodies weren’t preserved carefully like royals. Bodies of Moshe and the boy’s people were discarded, burned or left to rot.

It made the boy queasy, thinking of the great man he’d called father rotting in a heap, the last of his blood. Moshe had told him of his sister, who had been killed in a riot when she was a bit younger than the boy’s age. Miriam, she was called. She had called her people to arms, taking to the streets singing and playing the tambourine, her hair flying magnificently behind her. It hadn’t taken long for royal guards to put an end to her. The boy admired Miriam almost as much as he admired Moshe, but wouldn’t dare throw his life away like she had. No, he wanted to defy the cruel people that subjugated him in a far more dangerous way. Words, Moshe had told him everytime he complained about practicing his writing and begged to learn fighting, were far more powerful than any sword. The boy had always privately thought that was because Moshe had no experience sword-fighting, but now he could see that’d he been wrong.

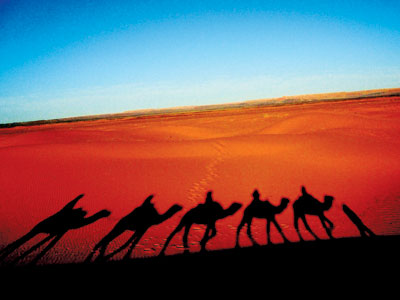

The boy knew not what waited in store for him, whether it be a hot hell worse than the Tophet he already lived in, or bliss granted to him by the supreme Lord of Moshe’s wise words, but he now had ambition. The boy would write the greatest story ever told, a story that would last far past Moshe’s and his own death. It would tell of the almighty God and the people that followed him, the people captured and enslaved by many, who managed to perservere through all. It would tell of the beautiful things God could create – a heaven on Earth – and the horrors he plagued down upon those who wronged. But it would also tell the story of Moses, the intrepid man who would lead his people to freedom, the man who would be God’s messenger. He sat on the sand, the sun sinking in towards the Pharoah’s palace like the gates of their hell on the horizon, the light illuminating the boy’s frame from behind. Tracing his finger in the sand, he began to write in the language of the suppressed a story that would liberate them:

“In the beginning, God created the Heaven and the earth.”

Similar Articles

JOIN THE DISCUSSION

This article has 2 comments.