All Nonfiction

- Bullying

- Books

- Academic

- Author Interviews

- Celebrity interviews

- College Articles

- College Essays

- Educator of the Year

- Heroes

- Interviews

- Memoir

- Personal Experience

- Sports

- Travel & Culture

All Opinions

- Bullying

- Current Events / Politics

- Discrimination

- Drugs / Alcohol / Smoking

- Entertainment / Celebrities

- Environment

- Love / Relationships

- Movies / Music / TV

- Pop Culture / Trends

- School / College

- Social Issues / Civics

- Spirituality / Religion

- Sports / Hobbies

All Hot Topics

- Bullying

- Community Service

- Environment

- Health

- Letters to the Editor

- Pride & Prejudice

- What Matters

- Back

Summer Guide

- Program Links

- Program Reviews

- Back

College Guide

- College Links

- College Reviews

- College Essays

- College Articles

- Back

Spindles

There had been more accidents that week than I could count on my fingers. I know this because I tried, silently marking the injuries one by one. My thumb was awarded to Mary who gouged her hand cleaning out the spindles when the string was knotted. Extending my index and middle finger, I devoted them to Willy and James. I went on until I got to poor George Johnson, paying homage to all the children, who accidentally stepped on a crooked rusty nail that stuck out of the floor. For the people working in the mills that day, his screeches echoed in all of our minds as we subconsciously traipsed through our daily life in our dreams that night. I marked two more people and decided to stop counting.

We sat in the front yard, the older kids, Caleb, George, Willy and I talking while the young ones finish their breakfast. We are given a pittance of food, definitely not commensurate with our work at the mill. The nine children in my house, including myself, are all orphans- victims of the same steamboat disaster that killed our parents, who were all on the boat at that time.

The young ones do not work as hard, yet they have the most hazardous occupation at the textile mill because they are too small to reach high, but their hands are just the right size to dangerously venture between the spindles upon request. Not favored, yet not diminutive as far as value in any way, the children never have time for play in the work day.

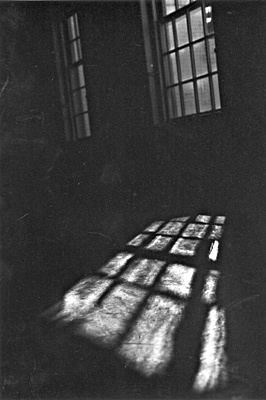

Looking to the north I see the factory, looming eerily in the distance. Barely making out the faint outline of the building, it has rectangular windows with bars on them lining the top of every cold concrete wall. The ground surrounding the prison-like mill is dirt with some scarce patches of grass and weeds.

Caleb looks towards the sun. He is the oldest at fifteen years old. "We go now. Sun's nearly up." All of us hold hands, intertwining our calloused and bruised fingers together down the road towards the mill to face another day together.

I close my eyes and tell myself what I say every day. I am here because I can't go anywhere else. I am here because I can't go anywhere else. I don't have my parents, and I don’t have family. This phrase comforts me in a way because I know I don't have hope and that things will change . . . consistent, normal. Every day is as uniform as the last.

It was middle afternoon in the textile mill, the sun was shining down on us through the ceiling windows and everyone was busy at work feeding thread through the machines, unknotting knots in fabric, transporting materials from place to place, and filling the steam-powered machines with water. We were being circumscribed by our usual overseer, Mr. Landing. Mary had been taking an unnecessary break and took a ride in one of the carts to transport materials moseying around the rooms inside the mill.

"Never do that again! Do you hear me? Do you hear me?" Berating Mary as she stumbled backwards, tears swimming behind her wide petrified eyes, Mr. Landing towered over her. He had entire volition of the punishment she would ultimately face. Trembling earthquakes rumbled through my shaky body. He was an overweight man with a red face who always had some sort of torture weapon in hand and was always profusely sweating.

"Mr. Landing, I'm sorry!" She wails, sobbing and backing into the corner, shrinking to the size of a newborn puppy.

I watched Mr. Landing raise a thick, heavy belt, savoring his transcendence over the petite four-year-old. It felt like I swallowed a gulp of sand and lodged a golf-ball down my throat. Looking away I heard a man's voice cry out in pain.

Caleb had taken another one of Mr. Landing's belts that he keeps in a big box in the corner and whipped him across the back. The decrepit 75-year-old man hunched over, weak and dilapidated.

In an instant, I knew I couldn't leave Caleb and or allow his heroic, intrepid plan fail. I wanted to be a part of the restitution that was imminent to happen.

I threw open the lid of the box on top of a small table that stood against the south wall of the big room, retrieved a thick belt and hurried to assist Caleb girding myself for what I was about to do.

All of the past memories I had of being beaten as a child seemed so vivid as adrenaline surged through me with a blast of energy and I raised the leather belt above my head with both hands.

I watched myself, outside of my own body. I saw the belt strike the back of his neck, reverberated from the sting of the slap, and felt his pain give me power.

Eventually after a few minutes I had to stop and comfort Mary.

Picking her up, carrying her like a baby and making my way to the front of the crowd, I saw all of the children observing in awe as Caleb had pinned the overweight man to the ground and tied the belt around his wrists. Other strong, older boys helped hold him down, as he was tied him up with at least 10 belts and flopping on the concrete ground like a fish out of water. All the children erupted with laughter, pointed and giggled. He had lost his macho in a matter of minutes.

"Stay on the ground you lazy loafer!" One child insulted punching his fist high in the air.

"Help! Help! Help!" Mr. Landing blubbered, howling, his voice traveling through the mill. Someone put a blindfold on him and on his mouth.

Leaving him squirming on the floor, Caleb got on top of a chair and whistled. "Everyone listen to me." The crowd's attention shifted to him as he gesticulated for everyone to gather around him quickly. There was no time for Caleb to be extolled (which he deserved) for his merits or to wait around until we got caught.

"Somebody help me!" He wailed. "Please help me!" 50 eyes stared at his body wriggling on the ground but nobody offered to help him.

Caleb pointed to the door that led to the warehouse and the throng quietly filed in. My heart was racing so fast I could feel my heart thrumming because I was so overjoyed. The owner would eventually manage his busy schedule abusing young children to supervise all of the overseers, so we needed to find a way to hide. The room was filled with boxes stacked and stacked on top of each other, tall ones, short ones, wide ones, all filled with garments. It felt like walking towards a crypt. I will surely die in one of those cardboard boxes.

I picked one filled with something made of wool, and maneuvered myself inside. The room was bustling, people trying to fit into the boxes, assembling their makeshift hiding places. Eventually, all I heard was quiet and the contrition began as I remained motionless in the dark.

"C'mon the act is up!" Mr. Carthage, the owner's voice boomed, bouncing off the walls of the room like red rubber balls jumping on untouched, shiny hardwood floor. Mr. Carthage undoubtedly discovered our tormenter in his awful state of confusion and discomfort eventually. Mary and I gripped each other's hands with white knuckles inside the four-foot by four-foot box half-filled with wool coats. We layered the thick material over us until we were sure we could not be seen if he happened to come upon our box. His voice was muted because of our insulation concealing us, but the intensity of his deafening yells shaking the room sent shivers rolling through me. My palms sweat and Mary's fingers shook with contained trepidation.

"Jana?" She murmered, her voice catching abruptly, clearly attempting not to start bawling again. The hot air and anxiety circulated inside the box and gnawed at my brain.

"Yes?" I whispered back.

A cry suddenly escaped her throat. "Jana it's my fault! I did this and now we are all going to pay!"

Footsteps… getting heavier and heavier and heavier.

"Hush Mary! Stop crying!" I comforted, covering her mouth with my hand. I had no time to commiserate.

The steps got closer and I closed my eyes tight and tried to retrieve the memory of my parents faces. They both had brown hair and my Mom had blue eyes.

I did not want the soothing repetition of my normal phrase. I wanted to feel like I had a life before,

The top of the lid opened and I felt a weight lift off of me, and it was veritable they were pulling garments out of the boxes.

I shut my eyes tighter and prayed they were watching me from heaven (maybe those Bible lessons James gave me might've worked).

The lid closed and the footsteps faded.

After a while I assumed it was night time.

I climbed out and saw someone peeking out of their box too, it was Caleb. He saw me and I quietly padded across the room with bare feet to reach the door. We would run away, probably. That's what Caleb promised me eventually. There were nice orphanages in a place called Chicago, but it was a long time away.

He tugged at the brass handle and rotated it to the left. It wouldn't move. He tried again, but nothing happened. My heart pounded against my rib cage.

The first emotion I felt was rage. Smoke billowing out of my ears, I thought of how they were warm in their beds tonight, stomachs full and their hearts content.

We both exchanged glances, and I searched his face for an answer. I found only eyes just as hopeless and scared as I was. Before I could open my mouth to devise a plan the doors creaked opened and Mr. Landing was there with Mr. Carthage. The two looked monolithic in the moonlight.

"What do we have here? Our little martyrs decided to go out for a little midnight snack."

The walking was the hardest part. My feet hurt awfully and the soreness was settling in quickly. "Caleb we need to stop." I panted, sitting down on the ground to rest.

Ever since we had been banished from the textile mill, we have been trying to find Chicago for a week, traveling northeast. It was because of our ingenuity and haltingly idiotic actions that we got thrown out on the streets. We were dissidents now, rebels on the run.

Caleb looked at me with disappointment. What we did would never be venial.

"Caleb! Jana!" Voices screamed in unison.

We both looked to the left down the road.

Seven children ran into my arms. I beamed at them and held them all close. They were all here. They found us.

I knew at that moment that I could go on forever until I reached Chicago because I had my family with me. If there is anything I've learned since I worked at the textile mill, it is that big machines have lots and lots of little parts. The orphans are my spindles. Spindles are not trinkets although they are small. With them missing I would be nothing. My fabric would be just string. They can never be abused or forgotten in my heart, because they are needed to keep me running on and on and on forever and ever.

Similar Articles

JOIN THE DISCUSSION

This article has 0 comments.